Broadway first met Tom Kirdahy on the arm of Terrence McNally, the legendary playwright who was his partner in life and art for over two decades. Today, Kirdahy stands as one of the industry’s most dynamic producing forces, with 21 Broadway credits and Tony Awards for shepherding Matthew López’s The Inheritance and Anaïs Mitchell’s still-packing-them-in hit Hadestown.

Even if those triumphs came from other writers, producing McNally’s considerable canon has been a throughline in Kirdahy’s career. That mission reaches a peak this week, as he reintroduces two of McNally’s Tony-winning works to new audiences—a big-screen Kiss of the Spider Woman starring Jennifer Lopez, out October 10 in theaters, and a major Broadway revival of Ragtime, opening October 16 at Lincoln Center Theater.

But that’s hardly his full docket. Kirdahy also leads the Jonathan Groff-fronted Just In Time, continues to nurture the off-Broadway rebirth of Little Shop of Horrors, and recently premiered Caroline, a powerful new play centered on a young trans girl.

Beyond Broadway, life and art have intertwined in fresh ways. Kirdahy has found love again with writer-musician Jon Richardson, who he met in his adopted second home of Provincetown, Massachusetts. Together, they’re building something new—Kirdahy’s company is supporting Richardson’s world-premiere musical The Jack of Hearts Club, which quickly sold out its run at the Provincetown Theater thanks to Richardson’s popularity as a local piano man.

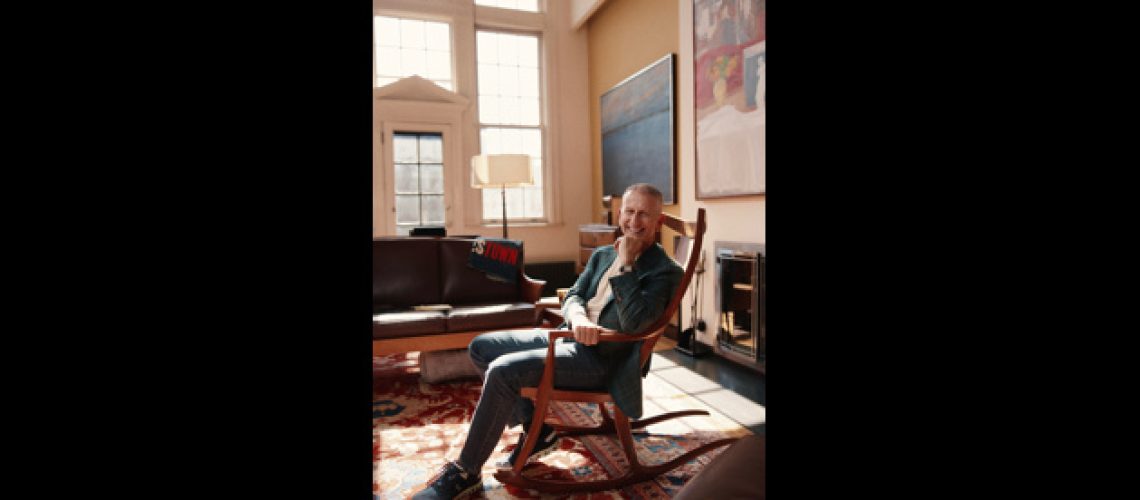

We met Kirdahy in the Greenwich Village apartment he shared with McNally for twenty years—on the block now officially named Terrence McNally Way—to talk about how legacy drives him, what renewal looks like, and why he still believes in the transformative power of theater.

This is a very special place we’re in. You’ve lived here since 2000 and spent 20 years here with Terrence. What is it like to be creating new work here?

It feels like a privilege. When Terrence died in March 2020, I was in Florida and didn’t return to the city until June. I’ll never forget walking into the building—one of the doormen saw me and just burst into tears. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to stay here. The world was shut down, I was alone. I felt Terrence’s embrace but honestly I just couldn’t stop crying. Now I love being in this space—and using it as a generative producer. Terrence loved making theater more than anything and now I love welcoming young artists into the home. We hold readings right in this living room all the time. A lot of art gets created in this space. It feels spiritually rewarding. And being in the Village—the home of the gay rights movement—is great. Artists and bohemians have always lived here. I love it.

That spirit drives the shows you’re passionate about. It’s in line with what Terrence cared about, too.

I think so. Kiss of the Spider Woman and Ragtime are both back, and it’s astonishing to think he wrote both in the ’90s because, while very different, they both feel timely. Terrence was ahead of his time—prescient. He had his finger on the pulse of the relationship between human rights, culture and government, and the way art can advance the human condition—or at least inspire people to live better lives.

Top: Jennifer Lopez; Bottom: Tonatuah & Diego Luna (Courtesy of Roadside Attractions)

Do you see yourself carrying on Terrence’s work as part of a larger mission? It’s important to intentionally keep a writer’s work in the canon.

It’s essential. But I’m also hoping I’m not the only one producing Terrence’s works, so I have to communicate to the world: come to me and ask if you can do Master Class or Love! Valour! Compassion! or The Lisbon Traviata or his other works. I want other producers shepherding his work. In addition to producing, we’ve created the Terrence McNally Foundation in his honor. With his royalties, we’re advancing LGBTQ+ rights in one silo of the mission. The other supports early-career playwrights. We have the Terrence McNally New Works Incubator with Rattlestick Theater, and plays from the incubator are starting to get produced everywhere. That would make him enormously proud. Even when he won his Lifetime Achievement Tony Award, Terrence made a point of saying to playwrights of the future, “This club has open membership and your diversity is welcome.” He always kept his eye on future writers. He didn’t want the club closed.

How did the Kiss of the Spider Woman movie come together, 30 years after its closing on Broadway?

In 2018, Bill Condon came to this apartment and met with John Kander and Terrence. He said, “I love Spider Woman and would love to make a movie.” Terrence said, “I want you to write it. I am not a screenwriter; I’m a playwright.” Terrence was a master of adapting novels or movies for the stage, so he was wise enough to say, “You’re a filmmaker. Do what’s right.” When Terrence died in March 2020, I wrote to Bill in June: “I can think of no greater way to honor his legacy than making this movie.” He wrote back within an hour: “I agree. Let’s do this.” Bill didn’t want to take any money—he wrote the screenplay on spec so we could retain artistic control. In 2023, he sent me the script. I went crazy for it and said, “I want to get this to Jennifer Lopez.” I called her agent, Kevin Huvane, and told him, “I never make these calls, but this is the one.” He read it within a week, agreed, got it to her—and a week later, she was in. Artists Equity—Ben Affleck and Matt Damon’s company—financed it, and it happened unbelievably fast.

It’s a real adaptation. It’s very different than the musical, but works beautifully on its own terms.

Yes. I love the movie. We did it with integrity. It’s a musical—we’re not running from that—and it’s very queer. The love story is not transactional in this version. There’s no doubt these two men have fallen in love. That was an active choice. Molina’s arc is right for our times. I don’t want to give it away, but “She’s a Woman” is very different in the film. I love what Bill has done.

Let’s talk about Ragtime, which opens next week at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre at Lincoln Center.

Honestly, it’s spectacular. I believe Ragtime has had a date with the Beaumont its entire life and has finally come home. It sits beautifully on that stage. Lincoln Center is our national performing arts center, the Beaumont our national stage and Ragtime an American masterpiece. I don’t know if that stage has ever had a production so soulful and so right for the moment. The cast is off the charts, the orchestra sounds great, Lear deBessonet’s direction is pristine. It’s not overproduced—it’s about human stories, not costumes. What you feel is deep love for these characters and their journeys—individual and collective—at the turn of the century, which may as well be right now. Someone asked if we had done any rewrites for 2025, but not a word or note has been changed. It just feels urgent and timely.

I’m amazed at how much is on your plate. Let’s talk about some of your other projects. Hadestown won the Tony Award for Best Musical and is now in its seventh year on Broadway. What’s the secret of its success?

The music and the universality of the themes. It was a competitive year when Hadestown opened—lots of experienced artists and well-known titles. People couldn’t even pronounce it! But the minute I heard the music, I knew I needed to produce it. Its themes endure—stories we need to tell again and again, to quote the show. And honestly, we continue to cast it well. This current company is jaw-dropping. I’m glad we haven’t done fear-based casting. Our first Hermes, André De Shields, was extraordinary, singular, Tony-winning. But then we went with Lillias White. We told the world from the start: we’re going to mix this up, surprise you, keep it fresh. It’s as fresh as when we opened.

Speaking of casting—let’s talk about Little Shop of Horrors. Honestly, some of your stars weren’t even familiar to me, but clearly well known with Gen Z!

True confession: same! Some names that cross my desk I’ve never heard of, but I have a young staff, which helps. The one thing I’ll say is we have a very rigorous team—Howard Ashman’s estate, Alan Menken, director Michael Mayer, everyone. We don’t just say, “Who has 10 million followers?” Everyone auditions, and everyone has to sign off. There’s a lot of quality control. I call the show the Miracle on 43rd Street.

You’re also experiencing great success with Just In Time. If I think about shows like that and Hadestown, they really offer audiences an escape to another world.

The goal is always the same—to make audiences feel transported when they enter the space and have a rich experience. Even with The Jack of Hearts Club, the musical my boyfriend Jon [Richardson] is doing in Provincetown, it’s set in a queer bar in 1963, and when audiences walk in, they feel transported.

Provincetown has long been a refuge for queer artists and was home to theater greats like Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill. I know you’ve found a second home there, as well as a new love.

After Terrence died, I sold our Hamptons home—I couldn’t be in that space anymore—and bought a place in Provincetown that reminded me of Love! Valour! Compassion!—lots of bedrooms with bathrooms. I was alone at the time, but I thought, I’m going to fill this house with my friends—not knowing I’d fall in love and life would twist again. Being in that queer artist community, in a place that celebrates art, free thinking and community, has given my heart a second act. I’ve never been happier. Provincetown is being very good to me.

When you embark on a new project do you ever think, WWTD—“What would Terrence do?”

I do, all the time. There’s another play I’m producing with MCC Theater about a mother and her trans daughter—Caroline by Preston Max Allen. When I read it, I thought, “Terrence would come back and murder me if I don’t do this—and if we don’t get it right.” The spirit of Terrence has informed every choice on that play. And, in true “you can’t make this up” fashion, on opening night I met Preston’s dad and turns out he took a playwriting class with Terrence at NYU. I thought, “OK, we’re good.” He also really wanted me to do Just In Time—he was still alive when Jonathan Groff started it. Terrence believed in Jonathan as an artist and understood what we wanted to do. When I flew out to meet Dodd Darin, Bobby Darin’s son, about securing the rights, he said, “Honey, go get them!” Opening night felt like his presence was there. In my Ragtime bio I say, “This one’s for Terrence,” because he always wanted it at the Beaumont. He fundamentally understood a show of that scale belonged on that stage.

Now that you have some distance from Gypsy [which closed in August], how do you look back on that production?

I miss it. I went a few nights a week—at least to see the second act. Any chance to see Audra McDonald do “Rose’s Turn.” I felt like I was watching greatness. We don’t always get those opportunities and I don’t use that word lightly. I feel like that’s happening at the Beaumont too—moments you’ll remember for the rest of your life. With Gypsy, we changed the landscape. We busted the door open and shattered the ceiling. No one will ever view Gypsy the same. Everyone will understand they can play these roles—which is kind of my life’s work. I wish we’d been more successful commercially, but it was a legacy project.

Before producing, you spent almost two decades as a lawyer providing free legal services to people living with HIV and AIDS. That work led you to meeting Terrence and into the theater world. Does it still fuel your choices?

Definitely. I care deeply about justice. I want to make the world better for all of us. Emma Goldman said, “I don’t want to be part of your revolution if I can’t dance.” For me that means, while we’re changing the world, we have to find joy. Every night at Just In Time, people watch an out, queer man transform into Bobby Darin and spend an evening with him just wanting more. People from all walks go and leave as one community. That’s healing. I genuinely think people leave feeling better about being alive. There’s so much bad news—we have to find joy that energizes us so we can do the hard work of remaining committed to democracy, treating one another with kindness, not burrowing into silos but actually communicating.

What do you tell young people who want to become a part of Broadway?

I tell people it’s hard. [Laughs.] I joke that I provided free legal services to low-income people living with AIDS in the Bronx, so when I started producing I thought this would be a walk in the park. It’s not. It’s such hard work! The odds are stacked against getting anything right, but I wouldn’t trade it. Make sure you really love it. Have a passion for it. Understand there are a lot of roles—you don’t have to be onstage to be essential to the ecosystem—and it can be unbelievably rewarding. But know what you’re signing up for because it will deliver heartbreak along the way.

You’ve made a beautiful life in the theater. What do you want people to know about that life, and what it gives you?

I get stopped fairly often, in particular by young queer folks who say, “I saw The Inheritance and it changed my life,” or “I saw Hadestown and I felt seen.” I got a letter from a parent who took his child to Little Shop and said he’d never seen his son so happy. Those are the moments you carry with you. What we do matters. I feel a massive responsibility and take great joy in it. The minute I start taking it for granted, I’ll want to check out. Terrence gave me that gift. Near the end of his life, he couldn’t catch his breath. Getting into the theater took so much work. But the minute he sat down and the curtain went up, his heart opened. He never lost his enthusiasm for going to the theater. I hope I never lose it, either.